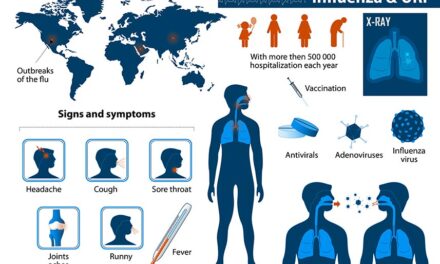

Staying well and maintaining a healthy immune system can sometimes be challenging. These challenges can be even more significant during the holiday season, for three distinct reasons. The first is that immune response does not tend to be as effective during the colder months of fall and winter compared to warmer months.1 Secondly, chronic stress can cause almost all measures of immune system function to drop across the board2— and who doesn’t have increased stress during the holidays? The third reason is that poor diet can compromise immune response3— and poor diet is also not unusual during the holidays. In fact, the intake of fruit and vegetables drops by about 12 percent in the winter months,4 and this is exacerbated around holiday times during which overeating patterns are well established and are commonly seen to involve protein foods, starchy foods and sugary desserts.5 And speaking of sugary desserts, research in which blood drawn from normal human subjects after they consumed glucose, fructose, sucrose, honey, or orange juice demonstrated a weakened immune response (significantly reduced capacity of certain white blood cells to battle bacteria).6 Of course the last thing you want is to get sick during the holidays, yet upper respiratory tract infections (e.g., colds, flu, etc.) occur more frequently during the cold winter months.7

Oh well, that’s life. Nothing much you can do about it, right? In fact, there is a great deal you can do about it if you focus on promoting a strong, healthy immune system during the holidays and beyond. Besides taking care to maintain a healthy diet, the use of specific nutraceuticals can make a significant difference. This article will address those nutraceuticals.

THE IMMUNE SYSTEM

A good place to start the discussion is by defining the immune system. According to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases: The immune system is a network of cells, tissues, and organs that work together to protect the body from infection. The human body provides an ideal environment for many microbes, such as viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites, and the immune system prevents and limits their entry and growth to maintain optimal health.8

Immune defenses may be divided into two broad categories: innate and adaptive. Innate immunity is the early phase of host response to infection, in which innate mechanisms recognize and respond to the presence of a pathogen. Innate immunity is present in all individuals at all times, does not increase with repeated exposure to a given pathogen, and discriminates between a group of related pathogens.9

Adaptive immunity is the response of antigen-specific lymphocytes to antigen, including the development of immunological memory (e.g. antibodies). Adaptive immune responses are generated by clonal selection of lymphocytes. Adaptive immune responses are distinct from innate and nonadaptive phases of immunity, which are not mediated by clonal selection of antigen-specific lymphocytes. Adaptive immune responses are also known as acquired immune responses10.

Ideally, in promoting a strong, healthy immune system, the goal should be to support both innate and adaptive immunity. Vitamin C,11,12,13 zinc,14,15,16 selenium,17,18 beta 1,3/1,6 glucan 19,10 and Echinacea20,21 are nutraceuticals that can help you to do that.

VITAMIN C

Consider that vitamin C has been shown to affect various components of the human immune response, including antimicrobial and natural killer cell activities, and lymphocyte proliferation. For the most part, the studies involved healthy, free-living populations who supplemented with 200 mg–6 g a day of vitamin C in addition to dietary vitamin intake. Hence, the results relate largely to the pharmacological range of vitamin C intakes rather than the nutritional range of intakes usually provided from food alone.23 It should also be noted that immune competent cells accumulate vitamin C, with a close relationship between the vitamin and immune cell activity, especially phagocytosis activity and T-cell function. Accordingly, one of the consequences of vitamin C deficiency is impaired resistance to various pathogens, while an enhanced supply increases antibody activity and infection resistance.24 In one randomized, controlled 5-year trial,25 those who took 500 mg/ day of supplemental vitamin C had a 66 percent lower risk of contracting three or more colds in a five-year period compared to those who took 50 mg/day of supplemental vitamin C. In another study,26 500 mg/day of vitamin C increased the SOD and catalase activities (powerful antioxidants) of immune cells known as lymphocytes. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, 31 percent of the U.S. population does not meet the estimated average requirement for vitamin C.27

ZINC

Zinc is essential for the integrity of the immune system, and inadequate zinc intake has many adverse effects.28 The immunologic mechanisms whereby zinc modulates increased susceptibility to infection have been studied for several decades. It is clear that zinc affects multiple aspects of the immune system, from the barrier of the skin to gene regulation within lymphocytes. Zinc is crucial for normal development and function of cells mediating nonspecific immunity such as neutrophils and natural killer cells. Zinc deficiency also affects development of adaptive immunity.29 Furthermore, in both young adults and elderly subjects, zinc supplementation decreased oxidative stress markers and generation of inflammatory cytokines.30 According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, 12 percent of the U.S. population does not meet the estimated average requirement for zinc.31

SELENIUM

Selenium is incorporated into a number of selenium-dependent antioxidant enzymes, also known as selenoproteins. These selenoproteins include glutathione peroxidases, which offer antioxidant protection against free radicals and other damaging reactive oxygen species.32 As such, there is much potential for selenium to influence the immune system. For example, the antioxidant glutathione peroxidases are likely to protect neutrophils from oxygen-derived radicals that are produced to kill ingested foreign organisms.33 Of particular interest is a 12- week human intervention study34 in which 119 volunteers took either a selenium supplement or a placebo daily to examine the response to an influenza vaccine. The results were that there was a heightened immune response in the selenium group (compared to placebo), further supporting the relationship between selenium status and immune function.

BETA 1,3/1,6 GLUCAN

A yeast beta 1,3/1,6 glucan derived from the cell wall of a proprietary strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been well researched, and its mechanism of action for this beta 1,3/1,6 glucan well documented. Once swallowed, immune cells in the gastrointestinal tract take up beta 1,3/1,6 glucan and transport it to immune organs throughout the body. While in the immune organs, immune cells called macrophages digest beta 1,3/1,6 glucan into smaller fragments and slowly release them over a number of days. The fragments bind to neutrophils, which are the most abundant immune cells in the body, via complement receptor 3 (CR3). In fact, neutrophils account for 40–60 percent of all immune cells. Beta 1,3/1,6 glucan primes and strengthens the key immune function of neutrophils that now move more quickly throughout the body. It is important to note that beta 1,3/1,6 glucan boosts immune function without over stimulating the immune system. Also, multiple human clinical studies have shown that this beta 1,3/1,6 glucan is effective in the treatment of upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) such as the common cold.

In a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial,35 250 mg/day of this beta 1,3/1,6 glucan or placebo was given to 100 healthy individuals during peak URTI season. The results were that beta 1,3/1,6 glucan decreased the total number of days with URTI symptoms by about 20 percent compared to the placebo group, and the ability to “breathe easily” was significantly improved in the beta 1,3/1,6 glucan group as well. Likewise, additional studies36,37 have shown that 250 mg/day of Wellmune WGP® this beta 1,3/1,6 glucan reduced URTI symptoms and improved mood state in stressed subjects, compared to placebo.

Since strenuous exercise is known to suppress immunity for up to 24 hours, another study38 with 182 men and women examined if 250 mg/day of this beta 1,3/1,6 glucan could positively affect the immune system of individuals undergoing intense exercise stress, and reduce URTI symptomatic days. The results were that it was associated with a 37 percent reduction in the number of cold/flu symptom days post-strenuous exercise compared to placebo, and was also associated with a 32 percent increase in specific immune cells. Other research39,40 has shown similar benefits with this beta 1,3/1,6 glucan in association with intense exercise. Also, in a study41 with firefighters, there was a lower incidence of URTI symptoms with perceived overall health significantly higher when supplementing with 200 mg/day of this beta 1,3/1,6 glucan compared to placebo.

In addition, a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study42 found that 250 mg/day of this beta 1,3/1,6 glucan for four weeks improved allergy symptoms, overall physical health, and emotional well-being compared with placebo in “moderate” ragweed allergy sufferers during ragweed allergy season.

ECHINACEA

Arguably, Echinacea is the granddaddy of all immune-enhancing herbs. It is excellent in helping to prevent and treat colds and influenza. Research reveals that Echinacea supports the immune system by activating white blood cells (lymphocytes and macrophages).43 Echinacea also increases the production of interferon, an immune component that is important in responding to viral infections.44 There are three species of Echinacea commonly used in herbal medicine: Echinacea purpurea, E. angustifolia, and E. pallida. This article will feature E. purpurea root.

Two different studies45,46 have examined the effects of short term use of E. purpurea root extract, equivalent to 930 mg/day. Results showed significant increases in T-cells (a type of immune cell). This is the type of quick response desired if you have a cold or the flu. This is also well within the approved dosage range of E. purpurea root approved by Health Canada47 (Canada’s version of the FDA) for use to help to fight off infections (especially of the upper respiratory tract), help relieve cold symptoms and shorten the duration of upper respiratory tract infections.

Several double-blind, clinical studies have confirmed Echinacea’s effectiveness in treating colds and flu.48 However, some research suggests that Echinacea may be more effective if used at the onset of these conditions.51,52 In a meta-analysis of 14 studies,53 researchers found that taking Echinacea cut the risk of catching the common cold by 58 percent, and if subjects already had a cold it decreased the duration by 1.4 days. In one of the studies, Echinacea taken in combination with vitamin C reduced cold incidence by 86 percent, and when the herb was used alone the incidence of cold was reduced by 65 percent. The bottom line is that when used appropriately, Echinacea is effective in preventing and treating the common cold.

CONCLUSION

These nutraceuticals can help support innate and adaptive immunity, and may help stave off URTI, or reduce their symptoms and duration during the holiday season and throughout the entire year. If URTI symptoms arise, however, it is important be aggressive, using the full amounts of vitamin C, beta 1,3/1,6 glucan and Echinacea discussed in this article, ideally in about three doses divided throughout the day.

References:

- Khoo AL, Chai LY, Koenen HJ, Kullberg BJ, Joosten I, van der Ven AJ, Netea MG. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 modulates cytokine production induced by Candida albicans: impact of seasonal variation of immune responses. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(1):122-30.

- Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull 2004;130(4):601-30.

- Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull 2004;130(4):601-30.

- Amanatidis S, Mackerras D, Simpson JM. Comparison of two frequency questionnaires for quantifying fruit and vegetable intake. Public Health Nutrition. 2001; 4(2), 233-239.

- Klesges RC, Klem ML, Bene CR. Effects of dietary restraint, obesity, and gender on holiday eating behavior and weight gain. J Abnorm Psychol. 1989;98(4):499-503.

- Sanchez A, Reeser JL, Lau HS, Yahiku PY, Willard RE, McMillan PJ, Cho SY, Magie AR, Register UD. Role of sugars in human neutrophilic phagocytosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1973;26(11):1180-4.

- Mossad SB. Upper Respiratory Tract Infections. Cleveland Clinic, Center for Continuing Education. Copyright ©2000-2014. Retrieved October 20, 2014 from http://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/infectious-disease/upper-respiratory-tract-infection/#s0015.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. Immune System. Last Updated January 23, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2014 from http://www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/immunesystem/Pages/default.aspx.

- Chapter: Principles of innate and adaptive immunity. Janeway CA Jr, Travers P, Walport M, et al. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. 5th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2001.

- Chapter: Principles of innate and adaptive immunity. Janeway CA Jr, Travers P, Walport M, et al. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. 5th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2001.

- Chapter: Principles of innate and adaptive immunity. Janeway CA Jr, Travers P, Walport M, et al. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. 5th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2001.

- Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Vitamin C. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press; 2000:117.

- Ströhle A, Wolters M, Hahn A. Micronutrients at the interface between inflammation and infection–ascorbic acid and calciferol: part 1, general overview with a focus on ascorbic acid. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2011 Feb;10(1):54-63.

- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2002.

- Prasad AS. Zinc in human health: effect of zinc on immune cells. Mol Med 2008; 14(5-6): 353-7.

- Shankar AH, Prasad AS. Zinc and immune function: the biological basis of altered resistance to infection. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998 Aug;68(2 Suppl):447S-463S.

- Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Vitamin C. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press; 2000:117.

- Arthur JR, McKenzie RC, Beckett GJ. Selenium in the immune system. J Nutr 2003; 133(5 Suppl 1): 1457S-9S.

- Santaolalla R, Abreu MT. Innate immunity in the small intestine. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2012 Mar;28(2):124-9.

- McFarlin BK, Carpenter KC, Davidson T, McFarlin MA. Baker’s Yeast Beta Glucan Supplementation Increases Salivary IgA and Decreases Cold/Flu Symptomatic Days After Intense Exercise. Journal of Dietary Supplements. 2013; EarlyOnline:1-13.

- Zwickey H, Brush J, Iacullo CM, Connelly E, Gregory WL, Soumyanath A, Buresh R. The effect of Echinacea purpurea, Astragalus membranaceus and Glycyrrhiza glabra on CD25 expression in humans: a pilot study. Phytother Res. 2007 Nov;21(11):1109-12.

- Brush J, Mendenhall E, Guggenheim A, Chan T, Connelly E, Soumyanath A, Buresh R, Barrett R, Zwickey H. The effect of Echinacea purpurea, Astragalus membranaceus and Glycyrrhiza glabra on CD69 expression and immune cell activation in humans. Phytother Res. 2006 Aug;20(8):687-95.

- Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Vitamin C. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press; 2000:117.

- Ströhle A, Wolters M, Hahn A. Micronutrients at the interface between inflammation and infection–ascorbic acid and calciferol: part 1, general overview with a focus on ascorbic acid. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2011 Feb;10(1):54-63.

- Sasazuki S, Sasaki S, Tsubono Y, Okubo S, Hayashi M, Tsugane S. Effect of vitamin C on common cold: randomized controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006 Jan;60(1):9-17.

- Khassaf M, McArdle A, Esanu C, Vasilaki A, McArdle F, Griffiths RD, Brodie DA, Jackson MJ. Effect of vitamin C supplements on antioxidant defence and stress proteins in human lymphocytes and skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2003 Jun 1;549(Pt 2):645-52.

- Moshfegh A, Goldman J, Cleveland L. What We Eat in America, NHANES 2001-2002: Usual nutrient intakes from food compared to dietary reference intakes. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service; 2005: 56 pgs.

- Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Zinc. Dietary reference intakes for vitamin A, vitamin K, arsenic, boron, chromium, copper, iodine, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, silicon, vanadium, and zinc. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2001:442-501.

- Shankar AH, Prasad AS. Zinc and immune function: the biological basis of altered resistance to infection. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998 Aug;68(2 Suppl):447S-463S.

- Prasad AS. Zinc in human health: effect of zinc on immune cells. Mol Med 2008; 14(5-6): 353-7.

- Moshfegh A, Goldman J, Cleveland L. What We Eat in America, NHANES 2001-2002: Usual nutrient intakes from food compared to dietary reference intakes. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service; 2005: 56 pgs.

- Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Selenium. Dietary reference intakes for vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium, and carotenoids. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press; 2000:284-324.

- Arthur JR, McKenzie RC, Beckett GJ. Selenium in the immune system. J Nutr 2003; 133(5 Suppl 1): 1457S-9S.

- Goldson AJ, Fairweather-Tait SJ, Armah CN, et al. Effects of selenium supplementation on selenoprotein gene expression and response to influenza vaccine challenge: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2011 Mar 21;6(3):e14771.

- Fuller R, Butt H, Noakes PS, Kenyon J, Yam TS, Calder PC. Influence of yeast-derived 1,3/1,6 glucopolysaccharide on circulating cytokines and chemokines with respect to upper respiratory tract infections. Nutrition. 2012 Jun;28(6):665-9.

- Talbott SM, Talbott JA. Baker’s yeast beta-glucan supplement reduces upper respiratory symptoms and improves mood state in stressed women. J Am Coll Nutr. 2012 Aug;31(4):295-300.

- Talbott S, Talbott J. Beta 1,3/1,6 Glucan Decreases Upper Respiratory Tract Infection Symptoms and Improves Psychological Well-Being in Moderate to Highly-Stressed Subjects. Agro Food Industry Hi-Tech. 2010;21:21-24.

- McFarlin BK, Carpenter KC, Davidson T, McFarlin MA. Baker’s Yeast Beta Glucan Supplementation Increases Salivary IgA and Decreases Cold/Flu Symptomatic Days After Intense Exercise. Journal of Dietary Supplements. 2013; EarlyOnline:1-13.

- Talbott S, Talbott J. Effect of BETA 1, 3/1, 6 GLUCAN on upper respiratory tract infection symptoms and mood state in marathon athletes. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine. 2009;8: 509-515.

- Carpenter KC, Breslin WL, Davidson T, Adams A, McFarlin BK. Baker’s yeast ?-glucan supplementation increases monocytes and cytokines post-exercise: implications for infection risk? Br J Nutr. 2012 May 10:1-9. [Epub ahead of print]

- Harger-Domitrovich SG, Domitrovich JW, Ruby BC. Effects of an Immunomodulating Supplement on Upper Respiratory Tract Infection Symptoms in Wildland Firefighters. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2008;40(5):S353.

- Talbott S, Talbott J, Talbott TL, Dingler E. ?-Glucan supplementation, allergy symptoms, and quality of life in self-described ragweed allergy sufferers. Food Science & Nutrition. 2013;1(1):90-101.

- See DM, Broumand N, Sahl L, Tilles JG. In vitro effects of echinacea and ginseng on natural killer and antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity in healthy subjects and chronic fatigue syndrome or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients. Immunpharmacol 1997;35:229-35.

- Leuttig B, Steinmuller C, Gifford GE, et al. Macrophage activation by the polysaccharide arabinogalactan isolated from plant cell cultures of Echinacea purpurea. J Natl Cancer Inst 1989;81:669-75.

- Zwickey H, Brush J, Iacullo CM, Connelly E, Gregory WL, Soumyanath A, Buresh R. The effect of Echinacea purpurea, Astragalus membranaceus and Glycyrrhiza glabra on CD25 expression in humans: a pilot study. Phytother Res. 2007 Nov;21(11):1109-12.

- Brush J, Mendenhall E, Guggenheim A, Chan T, Connelly E, Soumyanath A, Buresh R, Barrett R, Zwickey H. The effect of Echinacea purpurea, Astragalus membranaceus and Glycyrrhiza glabra on CD69 expression and immune cell activation in humans. Phytother Res. 2006 Aug;20(8):687-95.

- Monograph: Echinacea Purpurea. Health Canada, Natural Health Products Ingredients Database. Date Modified: 2013-07-10.

- Melchart D, Linde K, Worku F, et al. Immunomodulation with Echinacea-a systematic review of controlled clinical trials. Phytomedicine 1994;1:245-54.

- Blumenthal M, Hall T, Goldberg A, Kunz T, Dinda K (eds.). The ABC Clinical Guide to Herbs. Austin TX: American Botanical Council; 2003:88-96.

- Brinkeborn RM, Shah DV, Degenring FH. Echinaforce and other Echinacea fresh plant preparations in the treatment of the common cold. A randomized, placebo controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Phytomedicine 1999; 6(1):1-6.

- Melchart D, Walther E, Linde K, et al. Echinacea root extracts for the prevention of upper respiratory tract infections: A double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial. Arch Fam Med 1998;7:541-5.

- Grimm W, Müller HH. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of fluid extract of Echinacea purpurea on the incidence and severity of colds and respiratory tract infections. Am J Med 1999;106:138-43.

- Shah SA, Sander S, White CM, Rinaldi M, Coleman CI. Evaluation of echinacea for the prevention and treatment of the common cold: a meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2007; (7)7:473-480.