For the past two decades, fitness experts have been telling us that to get the benefits of exercise you had to do aerobics. And you had to work out hard. There was even a way to calculate whether your exercise was hard enough to do any good: You were supposed to subtract your age from 220, exercise intensely enough to get your heart rate up to 70–85 percent of that number and keep it there for twenty minutes.

Lose Weight, Get Healthy, And Live Longer

Now it turns out that the advice we were given was very far from the whole picture. “Moderate exercise can really produce enormous gains for health,” says Harvey Simon, MD, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Simon should know. He was one of the strongest advocates for the “more is better” philosophy that’s predominated in the fitness industry for the last twenty years. “I used to say that golf was the perfect way to ruin a four mile walk,” Dr. Simon says ruefully, “because it was only exercise at a moderate level, it didn’t bring your heart rate up and your walk is constantly interrupted. Then a study was published in the American Journal of Medicine that found men who simply added golf playing to their normal daily routine lost weight, lowered their girth and improved their cholesterol levels. That got me thinking.”

Dr. Simon began researching the literature and found that indeed moderate exercise had profound benefits. Then why had the experts touted heart-pounding heavy exercise for so long? “The problem had to do with what we call “end-points,” Dr. Simon said. “When you want to find out if something is working, you have to choose some specific end point to measure. So if, for example, you’re investigating a new teaching technique for reading, you want to measure whether kids actually read better. That’s the ‘end-point.’ The old studies on exercise were looking at the ‘end point’ of aerobic capacity—how much oxygen your lungs could hold and how efficiently your body used it, he explained. To improve that specific measure of fitness—called VO2 Max, indeed, harder aerobic exercise is needed. But when you look at the ‘endpoint’ of good health, a very different story emerges.

“I reviewed 22 studies, involving 320,000 people, that evaluated the impact of moderate exercise on cardiovascular disease and longevity,” Dr. Simon said. “The results were eye-opening. Moderate exercise was credited with 18.84 percent reductions in the risk of heart disease and 18.50 percent reductions in overall mortality. If you look at breast cancer, colon cancer, depression, heart attacks, stroke, sudden cardio death, diabetes, obesity, hypertension, even dementia, exercise is extremely beneficial,” said Dr. Simon, “and it doesn’t take aerobic exercise as traditionally defined to achieve those benefits.”

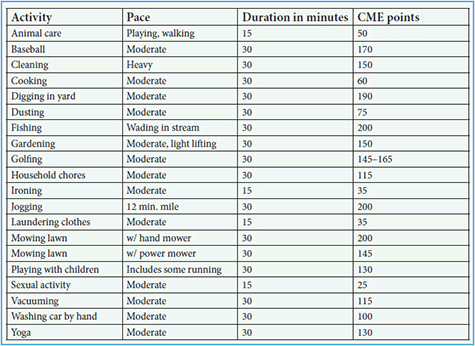

Dr. Simon, in his, The No Sweat Exercise Plan has come up with a term called “Cardiometabolic Exercise” to describe the kind of moderate exercise he’s talking about. “My theory is that all physical activities anywhere on the spectrum can benefit the heart and can benefit metabolism—things like blood sugar and body fat,” he said. In his book, Dr. Simon assigns points to various activities so that people can set a goal for how many points they need a week to achieve measurable health benefits. He calls these CME points (for Cardiometabolic Exercise). Dr. Simon recommends that you achieve 150 CME points per day or 1000 CME points per week to attain significant health benefits, but you can work up to that over the course of nine weeks starting with as little as 25 CME points per day. (See table on previous page of CME points for selected activities).

Walking is the core exercise in Dr. Simon’s “No-Sweat Exercise Program” and it gets a table all it’s own in the book. The number of CME points you get for walking depends on both your weight and on your speed, but typically a 160 pound individual would chalk up about 125 CME points for every 30 minutes of walking. “I’m not at all opposed to harder exercise,” Dr. Simon said, “and if people want to earn their 1000 weekly CME points by doing hard aerobics or weight training or sports, that’s just fine. The point of this is not that those exercises aren’t valuable, but that much more moderate exercise confers great benefits as well.”

Those benefits include 21.34 percent reduction in the risk of stroke, 15.50 percent reduction for dementia, 40 percent for fractures, 30 percent for breast cancer and 30.40 percent for colon cancer. “Many of these benefits were obtained with as little as 55 flights of steps a week, an hour of gardening, or two to four hours of light leisure time activity.” said Dr. Simon. “The little things really do add up.”

In one study, after just three weeks of inactivity, healthy twenty-year-old men developed many physiological characteristics of men twice their age. After just eight weeks of exercise there was an improvement in virtually every physiological and metabolic measure, including cholesterol, heart rate stiffness, digestion, muscle mass and metabolic rate. “Exercise is just the best anti-aging medicine we have,” Dr. Simon said.

From Bottom Line’s interview with Harvey B. Simon, MD, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and the founding editor of Harvard Men’s Health Watch. Dr. Simon is the award-winning author of five previous books on health and fitness, and received the London Prize for Excellence in Teaching from Harvard and MIT. His book is The No Sweat Exercise Plan (McGraw-Hill, 2006).