For decades vitamin B12 has been in use by the public, primarily for its role in supporting energy production—although it certainly has other functions and offers other benefits as well. Originally its delivery form was limited to capsules and tablets, but subsequently a sublingual (i.e. under the tongue) delivery form also became available. Following that, a coenzyme form of vitamin B12, known as methylcobalamin, was introduced and presented as a superior form over the commonly used cyanocobalamin form of vitamin B12. These various options have created some confusion over which delivery form and nutrient form are best to use. Add to this the fact that some individuals are more prone to vitamin B12 deficiency, and the confusion is compounded. This article will attempt to provide some clarification on these issues surrounding vitamin B12.

Vitamin B12 Coenzymes

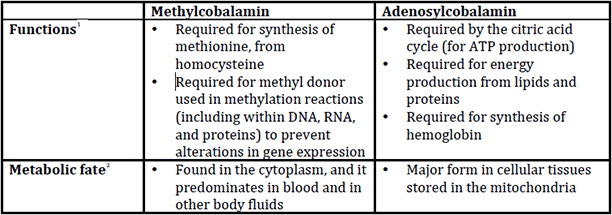

Vitamin B12 has two active coenzyme forms, methylcobalamin and adenosylcobalamin. In recent years, methylcobalamin has frequently replaced cyanocobalamin (regular vitamin B12) in dietary supplements as a result of the position taken that methylcobalamin is superior since it is an active form of B12. However, this position doesn’t take adenosylcobalamin into account. This is problematic since the functions of these two coenzymes and their metabolic fates are quite different:

Consequently, supplementation with methylcobalamin exclusively does not really address the functions of adenosylcobalamin—which are at least as important as those of methylcobalamin. For example, methylcobalamin doesn’t support energy production, while adenosylcobalamin does. Because of these differences, a recent article published in the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition stated, “Thus, it is prudent to use cyanocobalamin wherever required instead of methylcobalamin alone in order to address both the neurological and haematopoietic pathways.”3

The fact is cyanocobalamin can be converted into both methylcobalamin and adenosylcobalamin in the body. As a result, it can be argued that it may have an advantage over supplementation with methylcobalamin alone. Nor is there any concern that cyanocobalamin will not convert to methylcobalamin. According to a medical textbook, “There is no disease described in the human body where conversion of inactive cobalamin to active methylcobalamin is impaired. So there is absolutely no necessity to use methylcobalamin in place of cobalamin.”4

Vitamin B12 Deficiency

Vitamin B12 deficiency is uncommon in healthy individuals, although this nutrient does need some help being absorbed—whether from food or supplements. This help comes in the form of a glycoprotein secreted from the stomach called intrinsic factor (IF). The intestinal absorption of B12 is dependent upon its binding with IF. While most people produce sufficient IF, a condition known as atrophic gastritis, affecting 10–30 percent of people over 60 years of age,5 can cause intrinsic factor deficiency, which in turn can cause B12 deficiency due to malabsorption. 6 In addition, pernicious anemia, present in approximately 2 percent of individuals over 60 years of age,7 is the end stage of autoimmune inflammation of the stomach, causing decreased secretion of acid.

Furthermore, individuals with decreased stomach acid production may experience an overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria in the stomach, which can interfere with vitamin B12 absorption8 —and approximately 30 percent of the elderly have low secretion of stomach acid.9 Furthermore, diminished gastric function can result in bacterial overgrowth of H. pylori, which can significantly decrease vitamin B12 levels in serum, plasma, and gastric fluids.10

Other people who are at risk for vitamin B12 deficiency include individuals:11

- who have had bariatric surgery,

- with malabsorption syndromes such as celiac disease and tropical sprue,

- with pancreatic insufficiency,

- who are alcoholics,

- with AIDS,

- who have used acid-reducing drugs long-term,

- and who are vegetarian.

In fact, a review of studies just published in the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition12 has confirmed that vegetarians are particularly prone to vitamin B12 deficiency. Based upon age group, the deficiency prevalence was:

- 45 percent for infants,

- 0 to 33.3 percent for children and adolescents,

- 17 to 39 percent for pregnant women (dependent on the trimester),

- 0 to 86.5 percent for adults and the elderly.

The reviewed studies documented relatively high deficiency prevalence among vegetarians, especially vegans who do not ingest vitamin B12 supplements. The authors recommended, “Vegetarians, especially vegans, should give strong consideration to the use of vitamin B12 supplements to ensure adequate vitamin B12 intake.”

Sublingual Vitamin B12

In the early 1980s, Dr. Alfred F. Libby and his staff of researchers instituted a nutritional program of treating drug addicts, which Dr. Libby previously developed at a Southern California state hospital. Part of the program required therapeutic doses of vitamin B12. The problem was that some of these individuals may have had gastric issues, which precluded the use of a standard vitamin B12 tablet or capsule, and there were psychological contraindications to administering injections of B12 to addicts who normally used a syringe to inject heroin. Consequently, Dr. Libby and nutritional biochemists set about developing a sublingual delivery form which would bypass the IF issue by being absorbed directly under the tongue. Dr. Libby then tested the sublingual B12 on a group of patients, and included a control group. The results were that blood serum levels of vitamin B12 increased 90 percent in those patients supplemented with the sublingual B12. The control group experienced an average B12 decrease of 19 percent. From these results it was evident that B12 can be readily absorbed via the sublingual plexus and buccal cavity directly into the bloodstream.13

There are also other individuals in whom a standard vitamin B12 tablet or capsule is not the delivery method of choice. This includes some people with gastrointestinal disorders, diarrhea, vomiting, or who have difficulty swallowing standard oral tablets/capsules. This led researchers to conduct a study14 examining the effectiveness of sublingual vitamin B12 in 18 people (age range 23–80) with vitamin B12 deficiency. All patients were given sublingual lozenges of 1000 mcg cyanocobalamin twice daily for 7–12 days, after informed consent was obtained. The results showed that sublingual vitamin B12 normalized serum cobalamin concentration in all patients, with concentrations increasing as much as fourfold. A similar human study15 also found that sublingual vitamin B12 increase cobalamin concentrations by about three-fold.

Another study16 examined the use of sublingual vitamin B12 on subjects who ate a raw-food, vegan diet, many of whom had urinary markers of low vitamin B12 levels. After receiving treatment with vitamin B12 lozenges, there was a significant improvement in urinary markers suggesting that the sublingual vitamin B12 was effective in improving vitamin B12 levels. The authors of the study recommended that those eating a raw-food, vegan diet supplement with a vitamin B12 lozenge.

Conclusion

The use of methylcobalamin alone will not necessarily provide the benefits of adenosylcobalamin, so it is important to use cyanocobalamin to assure an adequate conversion into both coenzymes. Various gastrointestinal disorders can increase the risk of vitamin B12, and the sublingual delivery form can provide an effective means of supplementation in these instances.

References:

- Shane B. Folic acid, vitamin B-12, and vitamin B-6. In: Stipanuk M, ed. Biochemical and Physiological Aspects of Human Nutrition. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co.; 2000:483–518.

- Cooper BA, Rosenblatt DS. Inherited defects of vitamin B12 metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 1987;7:291–320.

- Thakkar K, Billa G. Treatment of vitamin B12 deficiency–Methylcobalamine? Cyancobalamine? hydroxocobalamin?—clearing the confusion. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69:1–2.

- Bhasker Y. Chapter 139: Methylcobalamin Versus Cyanocobalamin. In Medicine Update, Volume 23. Mumbai:The Association of Physicians of India;2013:635–7.

- Baik HW, Russell RM. Vitamin B12 deficiency in the elderly. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999;19:357–77.

- Neumann WL, Coss E, Rugge M, Genta RM. Autoimmune atrophic gastritis–pathogenesis, pathology and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(9):529–41.

- Carmel R. Megaloblastic anemias. Curr Opin Hematol. 1994;1(2):107–12.

- Shane B. Folic acid, vitamin B-12, and vitamin B-6. In: Stipanuk M, ed. Biochemical and Physiological Aspects of Human Nutrition. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co.; 2000:483-518.

- Champagne ET. Low gastric hydrochloric acid secretion and mineral bioavailability. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1989;249:173–84.

- Lahner E, Persechino S, Annibale B. Micronutrients (Other than iron) and Helicobacter pylori infection: a systematic review. Helicobacter. 2012;17(1):1–15.

- Carmel R. Cobalamin (Vitamin B-12). In: Shils ME, Shike M, Ross AC, Caballero B, Cousins RJ, eds. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:482–97.

- Pawlak R, Lester SE, Babatunde T. The prevalence of cobalamin deficiency among vegetarians assessed by serum vitamin B12: a review of literature. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2014 May;68:541–8.

- Libby AF, Starling CR, Josefson FH, Ward SA. The Junk Food Connection: A Study Reveals Alcohol and Drug Life Styles Adversely Affect Metabolism and Behavior. Orthomolecular Psychiatry 1982;11(2):116–27.

- Delpre G. Sublingual therapy for cobalamin deficiency as an alternative to oral and parenteral cobalamin supplementation. Lancet. 1999;354:740–50.

- Sharabi A, Cohen E, Sulkes J, Garty M. Replacement therapy for vitamin B12 deficiency: comparison between the sublingual and oral route. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003 Dec;56(6):635–8.

- Donaldson MS. Metabolic vitamin B12 status on a mostly raw vegan diet with follow-up using tablets, nutritional yeast, or probiotic supplements. Ann Nutr Metab. 2000;44(5-6):229–34.